21 September 2025 Loorentag with Camille Luscher

20 September 2025 Loorentag 2025

It was a lot of fun to show little videos about "The Magic Mountain" and one of Camille's mind-bending mind maps to illustrate our overriding point that translators not only needed to be made visible but needed to make themselves visible by campaigning, writing, posting, etc.

And most translators do that, but without centres such as Looren they would be deprived a hub to coalesce around. So congratulations to Gabi and her team in Wernetshausen for supporting us all!

13 September 2025 Reverse translation game

Two teams – the English > German translators Irma Wehrli and Niklas Fischer, and the German > English translators Chantal Wright and Simon Pare – had each selected a short translation in advance, which the other team saw for the first time as the game got underway. The teams then had 15 minutes to produce a reverse translation of a translation into their mother tongue. The aim of the exercise was to highlight the freedom and inventiveness of the translation process, to question the notion of the original, and, for the players, to produce something akin, but different, to the original.

As the teams worked, so did the audience, beavering away at their own version of whichever text they wished, or both, and raising questions at the end after each team had confronted its creation with the original.

Niklas and Irma were faced with a passage from Henry A. Smith's 1977 translation, with the title "The Woodchuck Hunt" of Ulrich Becher's 1969 phenomenal novel "Murmeljagd". Smith had sacrificed a number of the features of the text that made it so spritely in German, and this complicated the retranslation process.

Judge for yourselves:

"Well, gentlemen, how's the hunting?"

The one on his knees jerked his face towards me. A face not particularly handsome, but anonymous to agreeable. An attractive average-boy's face, his carefully parted ash-blond hair slicked down with brilliantine, his medium sideburns typical of the petty bourgeois Austrian dandy. In the hotel I had already noted this en passant, as well as the fact that the other fellow was straw blond.

The weasel-quick eyes of the ash blond were fixed on my left pants pocket. I moved the hidden stone into position like a "trigger happy" gunman in an American gangster film who enjoys shooting holes in his pocket.

The one with the agreeable face: "Hunting? Whad'ya mean, hunting?"

"Na, meine Herren, wie steht's mit der Jagd?"

Der Kniende wandte mir rückhaft das Gesicht zu. Ein nicht durchaus hübsches, indes eins von wenig sagendem bis gefälligem Aussehn. Ein ganz attraktives Jünglingsdutzengesicht, sorgsam gescheiteltes, mittels Brillantine angelegtes aschblondes Haar, die kleinbürgerlich-gigerlhaften 'Halbkoteletten' typisch austriakisch. Solches hatte ich bereits en passant im Hotel Morteratsch konstatiert, ebenso, daß der andre ein Semmelblöndling war.

Der wieselflinke Blick des Aschblonden traf meine linke Hosentasche. Ich brachte den hineingestopften Stein in Position wie ein Schießkünstler in einem amerikanischen Gangsterfilm, der triggerhappy, sich ein Vergnügen draus macht, mit einer seiner verschiedenen Pistolen durch seine linke Hosentasche zu feuern.

Der mit dem gefälligen Gesicht: "Jagd? Was für eine Jagd meinen S' denn?"

Irma and Niklas nevertheless did a sterling job.

Chantal and I got a passage from James Boswell's "Dr. Samuel Johnson: Leben und Meinungen. Mit dem Tagebuch einer Reise nach den Hebriden." Hrsg. und aus dem Englischen übersetzt von Fritz Güttinger. Diogenes, Zürich 2008. There were surprising turns of phrase that we couldn't reproduce, but there was agreement in the room that our retranslation did have the patina of the age.

6 June 2025 Conversation about creativity in translation at the ZHAW (Zurich University of Applied Sciences)

Thanks to Chantal for her invitation and excellent questions, and to the audience for putting up with my jokes.

22 August 2024 2024 Helen & Kurt Wolff Prize

It was my first translation published rather than simply distributed in the US and therefore the first time I'd been eligible for the prize.

Many congratulations to the winner, Jon Cho-Polizzi!

28 September 2023 Werkbeitrag, Kanton Zürich

It was great to read the opening few pages, describing Hans Castorp's arrival in Davos and his reunion with his cousin, Joachim Ziemssen, to an audience including family, friends and fellow translators.

1 December 2022 2022 Schlegel-Tieck Prize

23—30 October 2022 ViceVersa German<>English translation workshop, Looren (CH)

Brilliantly curated and led by Shelley Frisch and Miriam Mandelkow; deliciously catered for by Antonia Maino.

Heaps of helpful input on my submitted text 'The Lockmaster' by Christoph Ransmayr.

Lots of fun with texts by Olga Grushin, Georg Klein, Shida Bazyar, Carley Moore, Hermann Hesse, K-Ming Chang, Franz Jung, Sabrina Mahfouz and, last but not least, 'Finnegans Wake'.

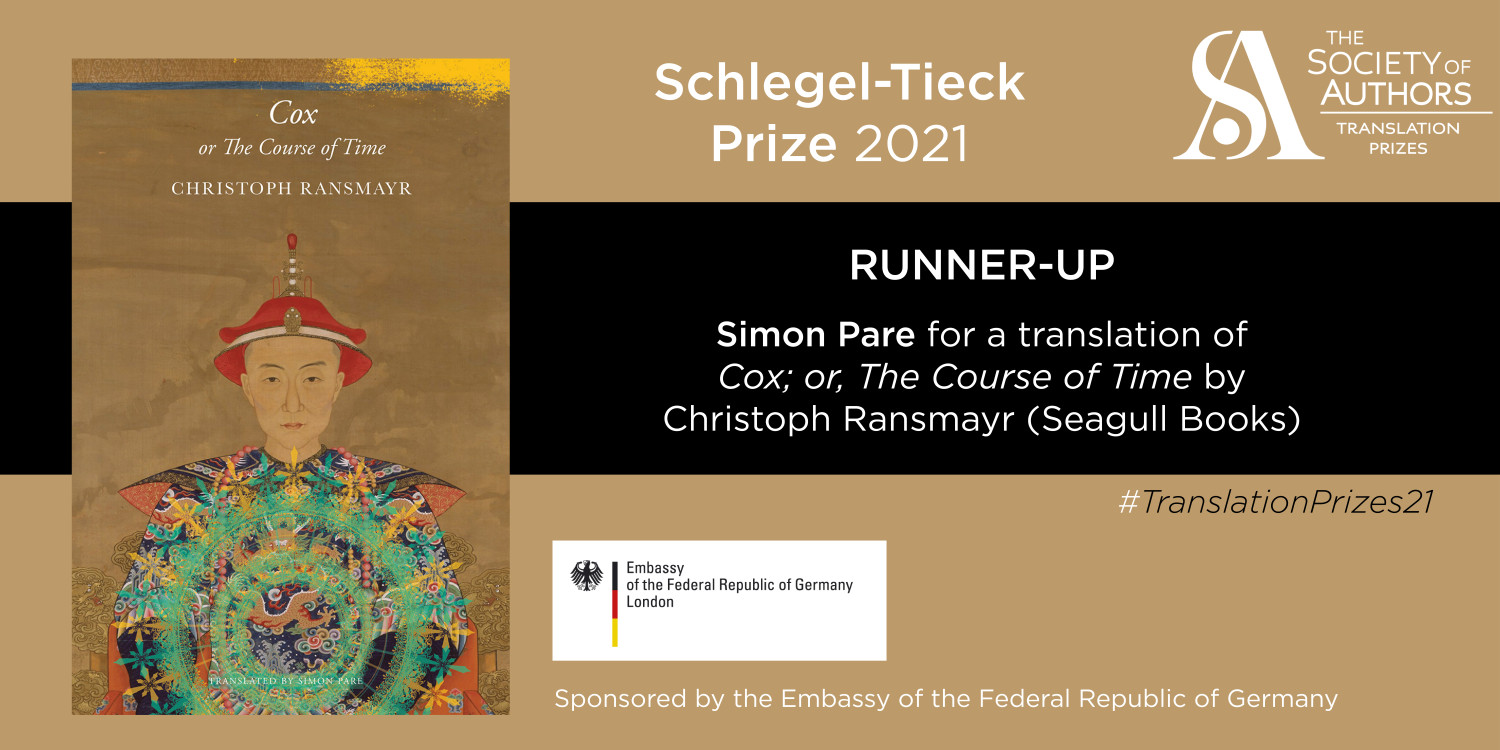

11 February 2022 Runner-up 2021 Schlegel-Tieck Prize

Many congratulations to the winner, Karen Leeder, for her translation of Durs Grünbein's "Porcelain: Poem on the Downfall of My City".

My thanks go out to the judges Jen Calleja and Alexander Starritt and to the Society of Authors, and I salute Seagull Books in Calcutta: the publisher Naveen Kishore as well as Sayoni Ghosh and Bishan Samaddar and, most affectionately, Sunandini Banerjee, my editor for this book and also the designer of the beautiful cover.

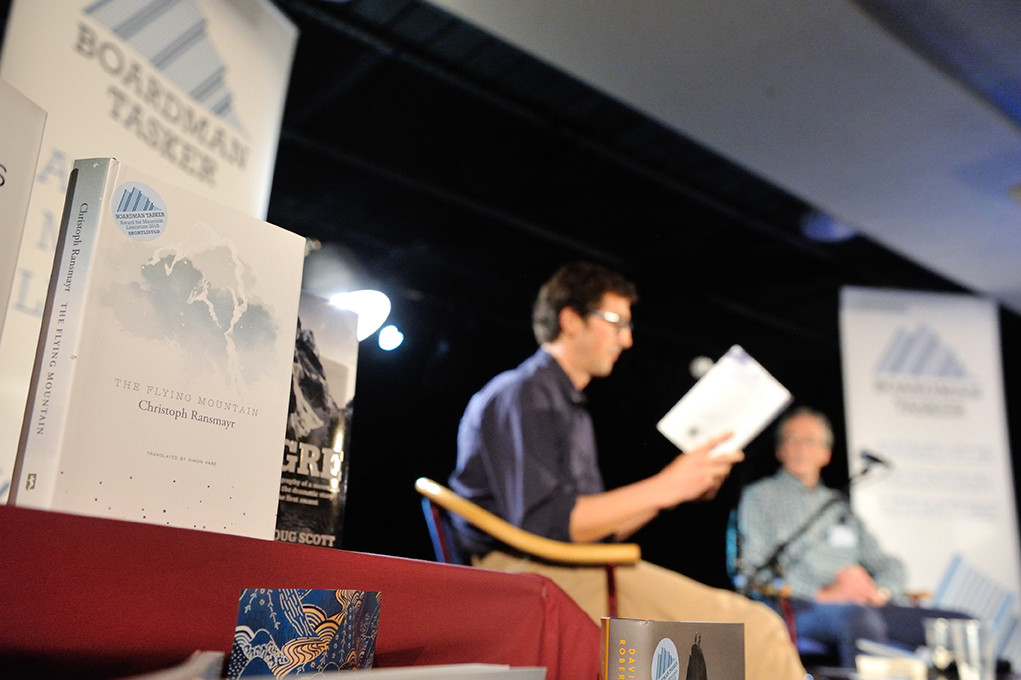

Look at the list of past winners and nominees, and it becomes clear that the person most responsible for a translator’s good fortunes is the author – in my case Christoph Ransmayr. John Woods won the Schlegel-Tieck in 1991 for his translation of "The Last World", and my English version of "The Flying Mountain" was shortlisted two years ago. Each of his books is an unusual and immensely enjoyable challenge.

Ransmayr deserves to be read and celebrated more widely in the English-speaking world, as he is in Germany and in other languages. Hopefully the publicity that accompanies the SoA Translation Prizes will bring him to people’s attention.

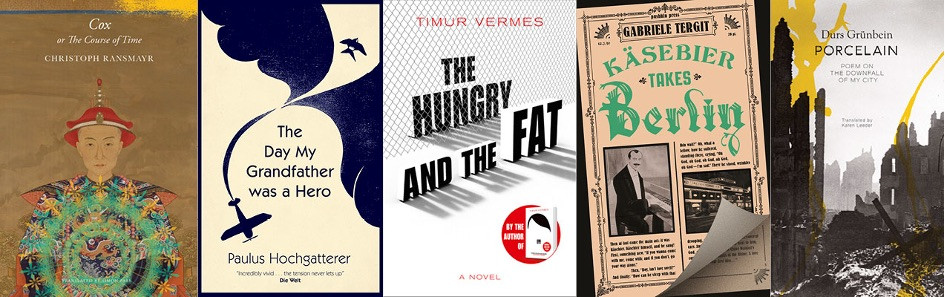

16 November 2021 2021 Schlegel-Tieck Prize shortlist

The other shortlistees are:

– Jamie Bulloch for a translation of "The Day My Grandfather Was a Hero" by Paulus Hochgatterer (MacLehose Press)

– Jamie Bulloch for a translation of "The Hungry and the Fat" by Timur Vermes (MacLehose Press)

– Sophie Duvernoy for a translation of "Käsebier Takes Berlin" by Gabriele Tergit (Pushkin Press)

– Karen Leeder for a translation of "Porcelain: Poem on the Downfall of My City" by Durs Grünbein (Seagull Books)

5 October 2021 Reading from "The Palace of the Wretched" by Abbas Khider

I contributed a passage from Abbas Khider's novel "The Palace of the Wretched".

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SRbTMt2aMGw

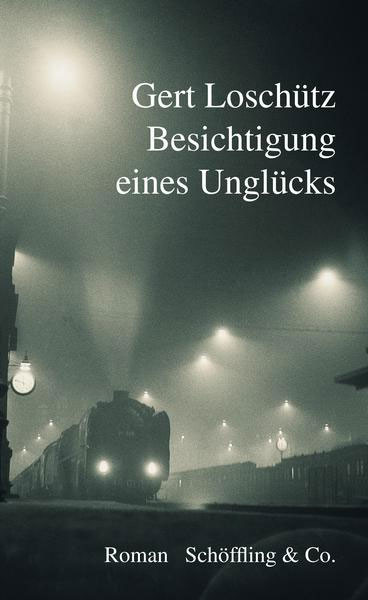

28 September 2021 Gert Loschütz wins Wilhelm-Raab-Preis

I have just handed in my translation of his previous novel "A Fine Couple" and look forward to working on this one sometime next year.

More in "Samples"

17—22 February 2020 Atelier de traduction ViceVersa au CITL Arles

Six seven-hour days of discussions with five Francophone and five Anglophone translators working on texts ranging from Langston Hughes of Harlem Renaissance fame to André Breton, a treatise on hunger to a YA novel, the poetry of Amy Clampitt, the dark humour of Donal Ryan, enslaved migrants on the shores of the Mediterranean, the French hinterland of Jeanne Benameur ... Such a wealth of registers to explore with our twelve-fold brain power.

Oh, and the light of Arles in February. Cycling in the Camargue. Vegetarian tiffin boxes out on the terrace. The beautiful Collège des traducteurs in a former cloister.

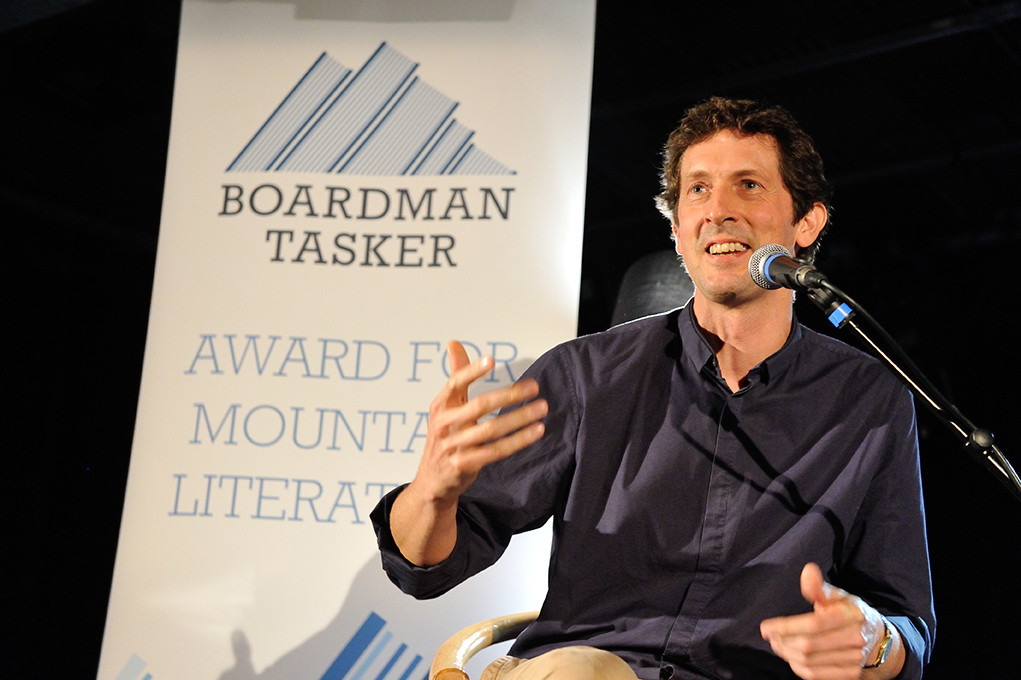

16 November 2018 2019 Boardman Tasker Award for Mountain Literature

Photos: Henry Iddon

11 June 2018 Straelen Most Promising Translator Prize

"Sometimes there comes along a translation that has such an ease and a fluency that it belies the original's deep complexity and linguistic challenges. Simon Pare's translation of 'Der fliegende Berg' is such a translation. Christoph Ransmayr's verse novel – and I will just pause here to repeat – Christoph Ransmayr's novel written in verse works at so many different levels. It is the story of two estranged brothers who come together following the death of their father, it is the story of how the one brother follows his sibling to climb a mythical mountain in farthest Tibet. It is the story of the politics of China in Tibet. It is the story of Ireland and Irish politics as seen through the eyes of their Catholic nationalist father. It is the story of a love affair between one of the brothers and a member of the Khampa clan with whom they travel to the mythical flying mountain, so named because the clan believe that the mountains were flown in from the sky and have to be nailed down to stop them floating away. It is a manual on how to – or how not to - climb a mountain. And it is a story where time and breath and snow and thought and fear and joy interleaf on one page, if not in one paragraph.

I won't even start on the challenges of translating a novel that is written in Flattersatz, because the fluidity of Simon's translation suggests that it took no effort at all. I won't talk about words, because that is the first tool that a translator must have in their toolkit, and Simon's toolkit is full to overflowing.

Instead I would suggest the most difficult challenge in translating this book is creating the world of the story. And this is what English does well. Our language is so flexible and free of rules that it is able to bring contradictory ideas and words into the same sentence without needing to pin them down precisely.

I had wanted to describe this world of the Flying Mountain as a tapestry, but a colleague yesterday – and excuse me while I segue for a moment to the joys of coming again and again to this house with so many wonderful colleagues - this colleague reminded me of a quote by Cervantes that says: a translation is like looking at a Flemish tapestry on the reverse side, for though the figures are visible, they are full of threads that make them indistinct, and they do not show the smoothness and brightness of the right side.

Who am I to contradict Cervantes, whose Don Quixote has been translated into 145 languages? And yet ... I would suggest that Simon has taken an exquisite meters-long tapestry by a master and re-woven it, strand for strand, in colours equally bright, with none of the knots or threads showing, so the viewer is roused to walk its entire length from left to right, inspired and enriched.

And for that achievement Simon Pare, we, the members of the jury, congratulate you."

Penny Black

12 June 2018

16 March 2018 10 Jahre Traduki

Bolted Places, Airy Halls

On the Translator’s Art

Occasionally, when he thought he was alone or at least unobserved, my father would hold long soliloquies in a mysterious language not a word of which I could understand. Probably a year or two before I learned to read and write I began to eavesdrop on these secret monologues from an undiscoverable hiding-place. It was only years later, after I had attended school for some time, that I gradually worked out that the guttural sing-song of those speeches, so different in tone from the Upper Austrian dialect in which I was praised, comforted or scolded, was the melody of the Russian language. My father spoke Russian when he was alone, but it will remain for ever a mystery to me whether this stemmed from an enduring love for a country and its literature, awoken in him at an early age by one of his secondary-school teachers in defiance of the rampant zeitgeist, or whether he was still under the spell of his memories of a prisoner-of-war camp on the Crimean peninsula near Sevastopol. But one summer’s day he died on a bench waiting for a bus, and the time for asking him questions was over.

Recalling my scheme to eavesdrop on his soliloquies, I see myself crouching behind a washing basket with bated breath, racked with guilty curiosity, and yet compelled to return again and again by the alluring magic of a language that seemed to me at the time to be the authentic idiom of adulthood, from which only children were excluded. This language, I believed, would over time accrue to everyone as naturally as height, grey hairs, a beard, baldness and all the other signs of maturity. I merely had to be patient, I needed only to wait, and one day I too would understand this melody. What I overheard from my den belonged to the vocabulary of the future.

My father’s favourite place for raising his secret voice was the ‘English closet’ of a teachers’ hostel, painted the same yellow as Schönbrunn Palace and built long before to mark his Apostolic Majesty Franz Joseph I’s seventieth jubilee; it accommodated the primary school teacher of my home village. Every day of my first few years at school I would walk across its gravel yard to the schoolhouse opposite, often hand in hand with my father, but each time, upon reaching an invisible boundary in the centre of the court, I was obliged to set aside all private forms of address and, with the respect demanded of every pupil, call my father ‘Mr Ransmayr’ and ‘Sir’ until we got home.

Yet when this gentleman changed back from a teacher commanding esteem, obedience and attention into a kindly man who pulled me on a sledge across snowy fields, told me stories and taught me to swim in the calm waters below the rapids of a nearby river, he would also revert to being a man who, like me, had to obey the call of nature and withdraw to the English closet from time to time. Then, whenever possible, I would take up position in an adjacent cabinet whose door also displayed the ‘00’ room number commonly used for lavatories, even though its seatless, dusty porcelain bowl served solely to hold a huge wicker basket. I would then listen through a hole in the wooden partition to monologues accompanied by the unspeakable, forbidden sounds of a taboo-laden physical performance – a trumpet-punctuated water music that made my nosiness seem even more wicked.

Patience! I was convinced that I merely had to wait and let time pass, growing bigger and older, until the mysteries of this strange language and all the other freedoms of adulthood would reveal themselves to me—freedoms so boundless that they would even erase the transgressions of youth.

I remember my disappointment when, after countless return journeys across the playground, I had finally mastered the whole alphabet and fully expected it to unlock any book I wished—and yet could only stare in bewilderment at a row of books from my father’s library, for despite my newly acquired skills I was incapable of deciphering even the titles on their spines.

When I eventually dared to ask my father for help, he read their embossed hieroglyphs as effortlessly as I did my textbooks, and for the very first time I heard the melody of his secret language elsewhere than in a forbidden place; and embedded in that melody I heard, also for the first time, names such as Dostoyevsky, Pushkin, Gogol, Turgenev and Gorki. My toils of the past months may have given me mastery of the Latin alphabet, I realised, but I was worlds away from understanding Cyrillic, Arabic, Hebrew, Japanese, Chinese and any of the countless other lines of characters in which the world’s many languages became writing.

I can only dimly recall the revelation of this Babylonian fact. Far clearer in my mind, however, is the associated, painful and sobering realisation that to gain an understanding of language and writing was either inextricably bound up with the effort of learning or else required help, and that gifts such as one’s mother tongue were the exception. Normally, every single word would have to be heard and parroted, spelled and repeated over and over and over again until eventually it assumed a stable sound, a meaning and a distinctive shape.

And today? Today I know that our capacity to decipher the languages, tales and symbols of other cultures, whether they be budding far away, blossoming next door or long since faded, can be gifted even to people trapped in their mother tongues – if they are assisted by translators, interpreters and teachers, who regard their services not as a luxury but as a necessary and precious tool for understanding the world. Without this aid, even great literature would, to the vast majority of readers or listeners, be not a polyphonic choir singing in airy halls but merely a name for a series of soliloquies in occupied, bolted places.

26—30 June 2017 15th Straelener Atriumsgespräch on 'Cox'

Previous guests include Günter Grass (who inspired these Straelener Atriumsgespräche with his famous ritual of convening his translators for each new novel), Julia Franck, Jenny Erpenbeck, Lutz Seiler and Uwe Tellkamp.

I was lucky enough to be invited as the English translator of Christoph Ransmayr’s 2016 novel 'Cox oder Der Lauf der Zeit' (S. Fischer) for Seagull Books (who also published my translations of his previous two books, 'Atlas of an Anxious Man' and 'The Flying Mountain'), and we were all fortunate that Christoph found time in his hectic travel schedule.

The size of the groups has varied from three to eighteen in the past, and this year there were six of us, the other translators hailing from Bulgaria, Croatia, Italy, Spain and China.

It is unusual for a Chinese translator to participate in the Atriumsgespräch, but for this book Han Ruixiang’s presence was both significant and extremely helpful. After all, Cox centres on a fictional encounter between a late-18th-century English clockmaker, Alister Cox, and the Emperor of China, who has summoned him to his court to fashion a number of unique clocks, each reproducing a subjective perception of time. It is a wonderful evocation of two men’s attempts to master the passing of the years, of love and loss, with occasional flashes of recognition and understanding piercing the mysterious veil of cultural and social differences.

Under the guidance of literary critic Insa Wilke, we started by addressing some general aspects of the novel (unorthodox punctuation, pronunciation and transliteration of Chinese terms, titles, etc.) before working our way through the book from first page to last, raising queries as we went. It is a short novel, and Christoph Ransmayr writes with great clarity, so progress was swift and we’d tackled all our queries by lunchtime on the second day. As a seasoned traveller, Ransmayr is extremely alive to the subtleties of translation and interpretation, and his overall message was that we could do much as we wished. He even provocatively suggested that we embellish his novel with some scenes of our own devising.

Ruixiang was troubled by the fact that some geographical details about China – the course of a river, the name of a sea – were deliberately distorted in the book: a Chinese reader wouldn’t understand. Christoph Ransmayr’s response? Change whatever needs changing! Other questions from Ruixiang went more to the heart of differing Western and Chinese worldviews. For example, why should a court mandarin feel trepidation when his sole function was to obey orders? And so, in translating, we experienced a little of Cox’s bewilderment faced with a foreign culture.

The trouble with gathering several translators working in different languages is that, in the absence of many difficulties of understanding, each of us was left with the problem of how to make the book sing in our particular language – and non-native speakers cannot help you with that. For languages less dense than German, the major challenge of reproducing Ransmayr’s writing in English is the need to unravel extremely long sentences while maintaining his singular cadence.

In general, I am convinced that translating is a very private pursuit, an individual grappling with a text. The great joy of collaborating in this way, though, is that people have interesting anecdotes to tell and unexpected areas of knowledge come to light. In our case, Andy Jelčic from Croatia turned out to be an expert on clocks, so we benefited from a potted history of clock mechanisms during a visit to the town museum.

The climax of the workshop was a public reading in the College’s wonderful atrium to a mixed audience of some eighty-five dignitaries, funders, local booklovers and resident translators. Christoph Ransmayr discussed the book and his admiration for translators, then read the first page of the novel, which describes Cox’s arrival by ship in Hangzhou Bay just as twenty-seven tax collectors are having their noses cut off on the quayside. Each of us then answered a question from the moderator before reading our own version of the same passage, creating a staggered chorus of Coxes, some intelligible to many, some a blaze of sound. Ransmayr read the rest of the first chapter – then drinks rounded off a collaborative, cosmopolitan occasion during which we had eaten together, laughed together, cycled through a nature reserve into Holland for pancakes and local beer, and talked literature, travel, poker, showjumping and other matters too numerous to mention.

It should be mentioned that Renate Birkenhauer kept detailed minutes which will serve as a record for the book’s future translators into other languages and colleagues who were unable to attend.

A final word about the Europäisches Übersetzer-Kollegium for those unfamiliar with it. As well as hosting the Atriumsgespräche, the centre is a fantastic place for translators (with a book contract) to come and work for anything from a couple of weeks to three months in the case of the translator-in-residence. I would like to thank Frau Dr. Regina Peeters and her kind team who think of everything, leaving you to enjoy the facilities (including the largest dedicated translation library in the world), the peace, the bikes (the surroundings are tabletop flat!) and a studious community of interesting, like-minded colleagues.

Article published in New Books in German