21 September 2025 Loorentag with Camille Luscher

20 September 2025 Loorentag 2025

It was a lot of fun to show little videos about "The Magic Mountain" and one of Camille's mind-bending mind maps to illustrate our overriding point that translators not only needed to be made visible but needed to make themselves visible by campaigning, writing, posting, etc.

And most translators do that, but without centres such as Looren they would be deprived a hub to coalesce around. So congratulations to Gabi and her team in Wernetshausen for supporting us all!

13 September 2025 Reverse translation game

Two teams – the English > German translators Irma Wehrli and Niklas Fischer, and the German > English translators Chantal Wright and Simon Pare – had each selected a short translation in advance, which the other team saw for the first time as the game got underway. The teams then had 15 minutes to produce a reverse translation of a translation into their mother tongue. The aim of the exercise was to highlight the freedom and inventiveness of the translation process, to question the notion of the original, and, for the players, to produce something akin, but different, to the original.

As the teams worked, so did the audience, beavering away at their own version of whichever text they wished, or both, and raising questions at the end after each team had confronted its creation with the original.

Niklas and Irma were faced with a passage from Henry A. Smith's 1977 translation, with the title "The Woodchuck Hunt" of Ulrich Becher's 1969 phenomenal novel "Murmeljagd". Smith had sacrificed a number of the features of the text that made it so spritely in German, and this complicated the retranslation process.

Judge for yourselves:

"Well, gentlemen, how's the hunting?"

The one on his knees jerked his face towards me. A face not particularly handsome, but anonymous to agreeable. An attractive average-boy's face, his carefully parted ash-blond hair slicked down with brilliantine, his medium sideburns typical of the petty bourgeois Austrian dandy. In the hotel I had already noted this en passant, as well as the fact that the other fellow was straw blond.

The weasel-quick eyes of the ash blond were fixed on my left pants pocket. I moved the hidden stone into position like a "trigger happy" gunman in an American gangster film who enjoys shooting holes in his pocket.

The one with the agreeable face: "Hunting? Whad'ya mean, hunting?"

"Na, meine Herren, wie steht's mit der Jagd?"

Der Kniende wandte mir rückhaft das Gesicht zu. Ein nicht durchaus hübsches, indes eins von wenig sagendem bis gefälligem Aussehn. Ein ganz attraktives Jünglingsdutzengesicht, sorgsam gescheiteltes, mittels Brillantine angelegtes aschblondes Haar, die kleinbürgerlich-gigerlhaften 'Halbkoteletten' typisch austriakisch. Solches hatte ich bereits en passant im Hotel Morteratsch konstatiert, ebenso, daß der andre ein Semmelblöndling war.

Der wieselflinke Blick des Aschblonden traf meine linke Hosentasche. Ich brachte den hineingestopften Stein in Position wie ein Schießkünstler in einem amerikanischen Gangsterfilm, der triggerhappy, sich ein Vergnügen draus macht, mit einer seiner verschiedenen Pistolen durch seine linke Hosentasche zu feuern.

Der mit dem gefälligen Gesicht: "Jagd? Was für eine Jagd meinen S' denn?"

Irma and Niklas nevertheless did a sterling job.

Chantal and I got a passage from James Boswell's "Dr. Samuel Johnson: Leben und Meinungen. Mit dem Tagebuch einer Reise nach den Hebriden." Hrsg. und aus dem Englischen übersetzt von Fritz Güttinger. Diogenes, Zürich 2008. There were surprising turns of phrase that we couldn't reproduce, but there was agreement in the room that our retranslation did have the patina of the age.

5—5 February 2025 "The Hermit Crab" by Katja Lange-Müller

22 August 2024 2024 Helen & Kurt Wolff Prize

It was my first translation published rather than simply distributed in the US and therefore the first time I'd been eligible for the prize.

Many congratulations to the winner, Jon Cho-Polizzi!

28 September 2023 Werkbeitrag, Kanton Zürich

It was great to read the opening few pages, describing Hans Castorp's arrival in Davos and his reunion with his cousin, Joachim Ziemssen, to an audience including family, friends and fellow translators.

23—30 October 2022 ViceVersa German<>English translation workshop, Looren (CH)

Brilliantly curated and led by Shelley Frisch and Miriam Mandelkow; deliciously catered for by Antonia Maino.

Heaps of helpful input on my submitted text 'The Lockmaster' by Christoph Ransmayr.

Lots of fun with texts by Olga Grushin, Georg Klein, Shida Bazyar, Carley Moore, Hermann Hesse, K-Ming Chang, Franz Jung, Sabrina Mahfouz and, last but not least, 'Finnegans Wake'.

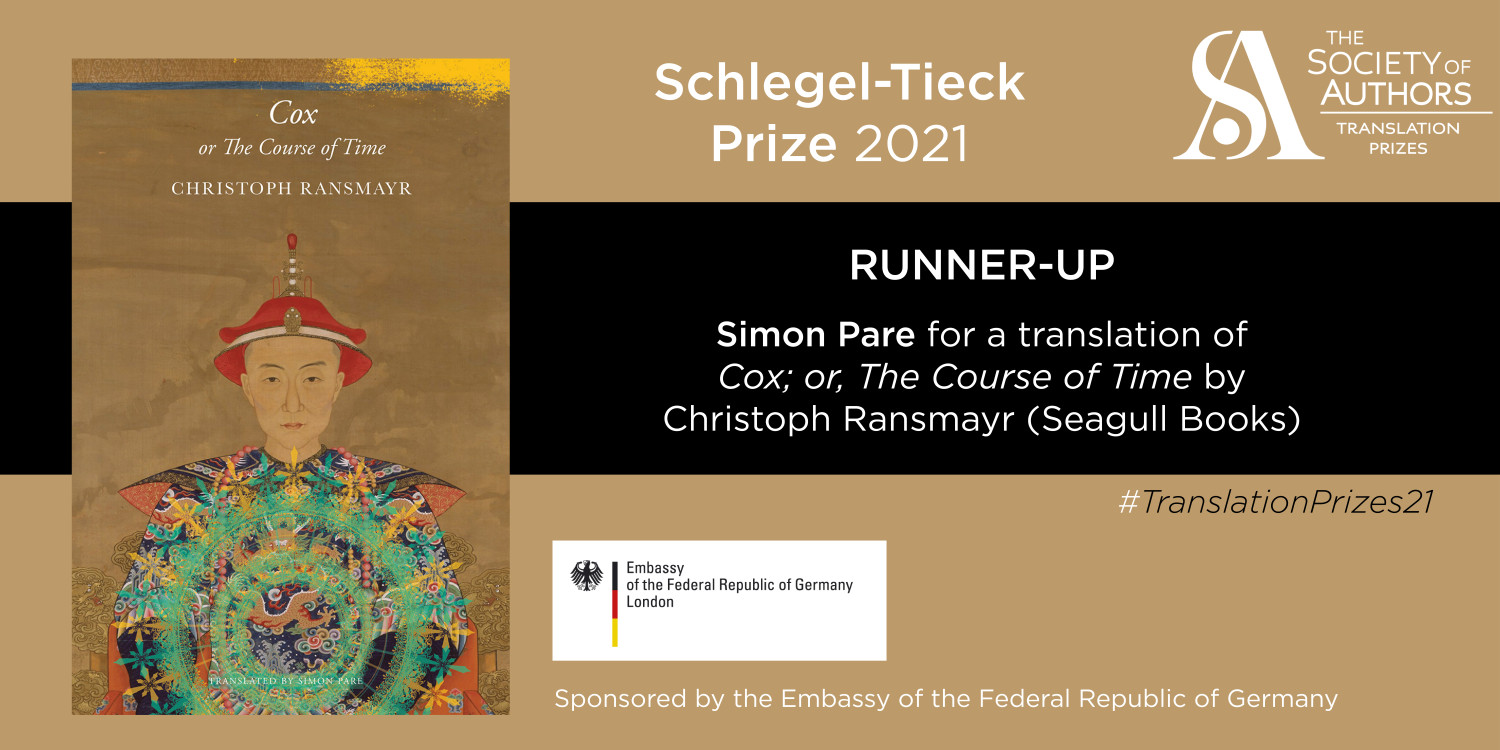

11 February 2022 Runner-up 2021 Schlegel-Tieck Prize

Many congratulations to the winner, Karen Leeder, for her translation of Durs Grünbein's "Porcelain: Poem on the Downfall of My City".

My thanks go out to the judges Jen Calleja and Alexander Starritt and to the Society of Authors, and I salute Seagull Books in Calcutta: the publisher Naveen Kishore as well as Sayoni Ghosh and Bishan Samaddar and, most affectionately, Sunandini Banerjee, my editor for this book and also the designer of the beautiful cover.

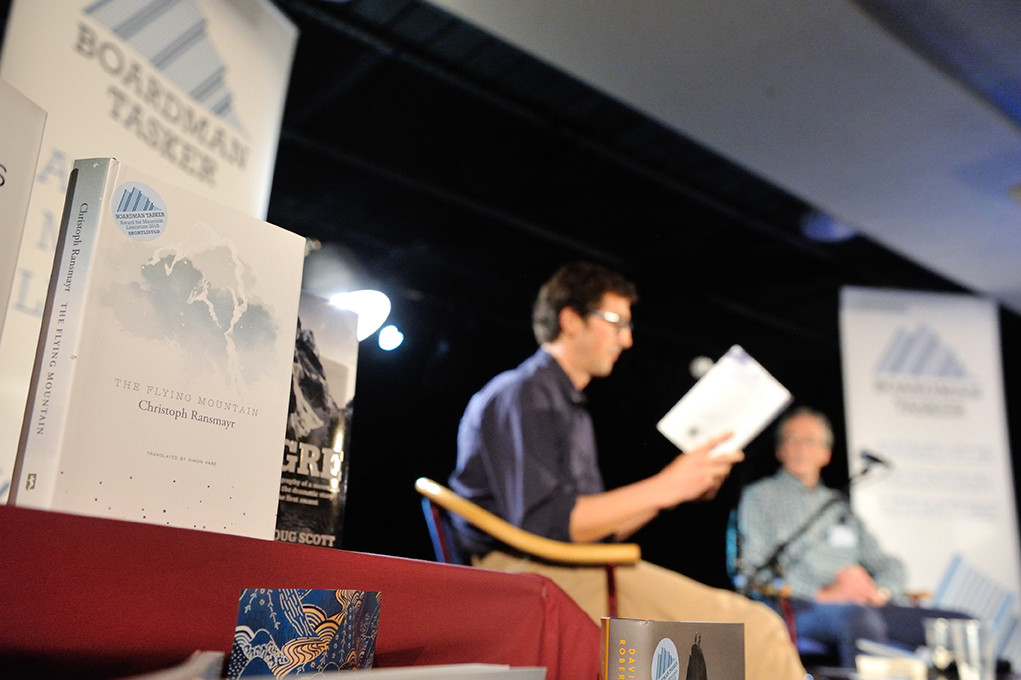

Look at the list of past winners and nominees, and it becomes clear that the person most responsible for a translator’s good fortunes is the author – in my case Christoph Ransmayr. John Woods won the Schlegel-Tieck in 1991 for his translation of "The Last World", and my English version of "The Flying Mountain" was shortlisted two years ago. Each of his books is an unusual and immensely enjoyable challenge.

Ransmayr deserves to be read and celebrated more widely in the English-speaking world, as he is in Germany and in other languages. Hopefully the publicity that accompanies the SoA Translation Prizes will bring him to people’s attention.

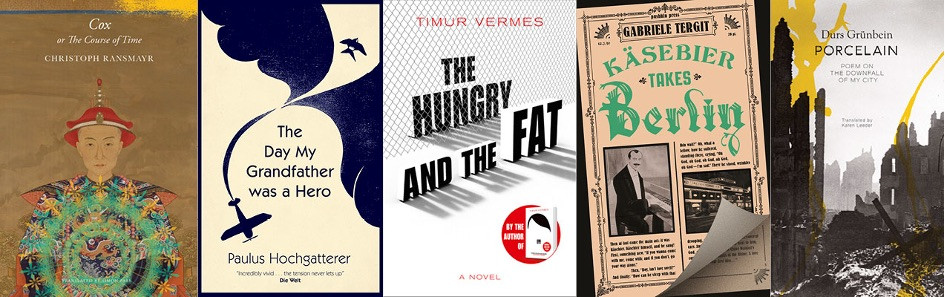

16 November 2021 2021 Schlegel-Tieck Prize shortlist

The other shortlistees are:

– Jamie Bulloch for a translation of "The Day My Grandfather Was a Hero" by Paulus Hochgatterer (MacLehose Press)

– Jamie Bulloch for a translation of "The Hungry and the Fat" by Timur Vermes (MacLehose Press)

– Sophie Duvernoy for a translation of "Käsebier Takes Berlin" by Gabriele Tergit (Pushkin Press)

– Karen Leeder for a translation of "Porcelain: Poem on the Downfall of My City" by Durs Grünbein (Seagull Books)

5 October 2021 Reading from "The Palace of the Wretched" by Abbas Khider

I contributed a passage from Abbas Khider's novel "The Palace of the Wretched".

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SRbTMt2aMGw

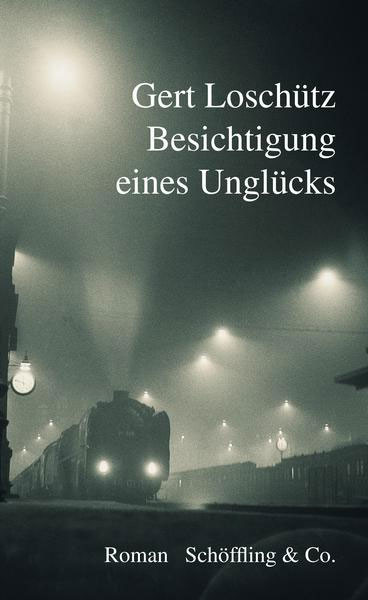

28 September 2021 Gert Loschütz wins Wilhelm-Raab-Preis

I have just handed in my translation of his previous novel "A Fine Couple" and look forward to working on this one sometime next year.

More in "Samples"

3 September 2021 Exhibition "Max Frisch und das Schauspielhaus Zürich", 23.08.2021 – 31.03.2022

© ETH-Bibliothek, Bildarchiv

18 April 2021 'Die Bagage' and 'Vati' by Monika Helfer

160 pp.

'Vati' — Hanser 2021

176 pp.

I read Monika Helfer's 'Die Bagage' ('The Riffraff') back in early 2020 around the time it became a bestseller. A slender novel about a dirt-poor, marginalised family in the Austrian Alps during the First World War, I found it hugely evocative of a life of outcasts in a small village, completely reliant on their own resourcefulness and scraps of neighbourly kindness. Despite the harshness of the setting and the parents’ relationship, the woman gains a glimmer of light in the form of a passing German - even though their child, the author's mother, was never spoken to by her father.

Now Monika Helfer has written a new novel-cum-memoir about her 'Vati' or Dad. It is even better, full of funny descriptions of the members of her mother's clan, who stick together through their consistent afflictions, and poignant in its portrayal of Helfer's father. He is an endearing but ultimately tragic figure, a booklover who establishes and then steals the library of the sanatorium for war victims - the dicovery of this theft leading to the whole family being cast out of their Alpine paradise.

6 February 2021 Max Frisch at Paradeplatz in Zurich in 1966

© Pia Zanetti/ Fotostiftung Schweiz / Codex Publisher, Produktion: Linkgroup /Printlink

1 October 2020 'Murmeljagd' by Ulrich Becher

700 pages

They've done it again.

After releasing a new edition of Gabriele Tergit's magnificent late-19th/early-20th-century family saga 'The Effingers', Schöffling have reissued two very different books by Ulrich Becher — 'Murmeljagd' (1969) and the 'New Yorker Novellen: Ein Zyklus in drei Nächten' (1950). Both are delightful discoveries and have been rightfully acclaimed in Germany, but I'll focus here on 'Murmeljagd', which was published by Crown in 1977 in an English translation by Henry A. Smith.

The blurb on my secondhand English edition (it is out of print) lauds a 'gripping and suspenseful novel by a man whose work has been compared with the best of Günter Grass and Alexander Solzhenitsyn', while Eva Menasse, in her afterword to the new Schöffling edition, explains that critics were bamboozled by Becher's fecund and anachronistic style, so out of step with the prevailing German literary generation of the late sixties, which of course included Grass. Menasse quotes reviewer Martin Gregor-Dellin as saying that Becher is 'so absorbed with his vocabulary and his exotic fest of storytelling that he loses his footing'. To which she responds that he may be losing his footing because his story is about the ground giving way beneath someone's feet.

It took me what seemed like an age to read 'Murmeljagd'. Two full summer months, but not once did I think of abandoning it. It was fascinating and frustrating, brimming with wordplay and tangents and capering characters and typographical oddities. Too much to devour; to be savoured in small helpings. A grotesque farce about life and death.

Albert — known by his name in reverse, Trebla — is an Austrian social democrat and WWI fighter pilot still scarred from a shot to the head during a dogfight, and in the opening pages of the book he skims across the border into Switzerland, outpacing two German skiers and dodging their bullets. Having been on the losing side during the 1934 civil war and persistently imprisoned, he is a wanted man.

In the idyllic Engadine valley, he is beset by dangers both real and imagined. News filters through to him of the Spanish Civil War and the threatening Reich, his father-in-law has been detained and his best friend murdered in a concentration camp, while he is simultaneously summoned to Zurich to renew his visa (exposing himself, he fears, to the risk of deportation back to Austria), investigates German twins whom he suspects of having been sent to assassinate him but who claim to be hunting marmots (or woodchucks, in US parlance), and unhelpfully finds himself in the vicinity of several suicides by drowning or shooting.

Trebla's present tribulations are constantly interrupted by bad news, but he is also taking ephedrin, a strong hay-fever drug which gives him hallucinations and intensifies his paranoia. There are, for example, two notable scenes when he is visited by the dead. One features a procession among the fish when he imagines plunging into the waters of a lake; the other is on a long nighttime march home, as a mysterious car races up and down the road and he is visited by the ghosts of his past. Becher continually uses the term 'Geisterbahnfahrt' — 'a ride on a ghost train'.

It is a stunning evocation of the precarious position of Switzerland, its inhabitants and those who sought refuge in the country as the Reich wraps its tentacles around Europe.

Arguably, however, it is neither this tense atmosphere nor the plot, veering wildly this way and that, that truly set this text apart. What dazzles is Becher's use of language, shot through with dialect, puns, associations, nicknames, inventive curses and jokes, telegrams, newspaper headlines, songs and stenographic notes, all picked out by the oddest use of italics and hyphens.

Becher's dialogues testify to his past as a playwright, but so does his faculty for striking visual imagery, the crowning achievement in this regard being Trebla's reception of the news of how his father-in-law, Giaxa aka 'der Rosenvater', a circus showman, perished in Dachau. In one of the most striking and horrifying images of individual death in the Nazi era - reminiscent of scenes in Curzio Malaparte's novel 'Kaputt' - Giaxa performs tricks on the camp commandant's fine horse, culminating in both rider and horse stranded and charred high on the camp's electric perimeter fence.

The fact that this story is told by Valentin, a Dachau escapee, as he plays billiards on top of a castle overlooking a dark ravine, before taking a fatal flight to participate in the Spanish Civil War... and that Trebla has been kissed, earlier in the evening, by a Spanish aristocrat who has mistaken him for Valentin... simply goes to show how fantastical and absurd this novel is. And these fantastical absurdities come thick and fast, overwhelming the reader.

There must be a UK or US publisher with the nous to republish this masterpiece.

1 July 2020 Zurich

"Zurich could be a charming little town. It lies at the lower end of a pretty lake whose hilly shores are not disfigured by factories but very much so by villas . . . I am especially enchanted by the location of its little town which is embraced from both sides by placid hills and natural forests that tempt you out on country walks, and in its centre sparkles a small green river, which indicates the direction of the great oceans (as every water course does, of course) and thus it always inspires a sensation of life, a yearning for the wider world, for coastlines . . .

There are also, as you hear in the streets, foreigners from all over the world. It is no accident that Zurich's coat of arms is blue and white; in the stark light of its föhn-fueled blue, which, adorned with the white of the gulls, is said to cause even the locals frequent headaches, this Zurich really does have a magic of its own, a "cachet" that is to be sought more in the air than anywhere else, simply a sparkle in the atmosphere, which stands in sharp contrast to the moping nature of the local physiognomy, and something out-and-out festive, something sonorous, something neat and tidy like its coat of arms, something blue and white with no conspicuous characteristics. It is, you might say, a town which derives its charm largely from the scenery, and at any rate you can understand the foreigners who get out on the embankment and take some pictures before they travel on to Italy, and you can understand the locals, who are proud when lots of pictures are taken. Its narrow lake, roughly the width of the Mississippi, curves glinting like a crooked scythe cutting through the green, undulating landscape. Even on weekdays, it is teeming with little sailing boats. Amid all the bustle, there is something spa-like about this Zurich, a traders' meeting place. The Alps are not as close as they are on the postcards, luckily; at a seemly distance they cap the swell of the foothills, a crowning surf of permanent white snow and bluish cloud."

9 April 2020 A lockdown letter to Samuel Pepys

Samuel Pepys FRS Esq.

St Olave’s Church

Hart Street

London EC3R 7NB

Lieber Samuel,

gestatten Sie, dass ich Dich duze und Samuel nenne? Eine Billigung Deinerseits werde ich nicht bekommen: ich lebe mehr als 300 Jahre nach Dir. Ich erlaube mir diese Freiheit, von Engländer zu Engländer, denn aus Deinen bekannten Tagebüchern geht der Eindruck hervor, dass Du einen zugänglichen und aufgeschlossenen Typ warst, der gleichermaßen mit König Karl dem Zweiten verkehren und mit den Wirten und Trinkern Deines Londoner Viertels unkompliziert tratschen konntest.

Warum ich jetzt an Dich denke? Wir sind heutzutage mit einer unerhörten Epidemie konfrontiert, die uns verwirrt und belastet. Während des Wütens der Großen Pest von London hast Du Deine Beobachtungen aufgezeichnet und jetzt war ich neugierig, Dein Tagebuch zu lesen und Dir von den Anklängen und Unterschieden zu berichten. (Es beglückt Dich, nicht wahr, dass Deine täglichen, rasch in einer akribischen Schrift notierten Bemerkungen noch im 21. Jahrhundert Leser finden? Gesamtausgaben, Auswahleditionen. Stell dir vor, sogar einen »erotischen« Pepys gibt es!)

In diesen Tagen wird dennoch viel eher der Bestseller 'Die Pest zu London' von Deinem Fast-Zeitgenosse — aber kein Zeitzeuge — Daniel Foe erwähnt; sein Buch zählt zu den aktuellen Literaturtipps. Warum Foes Aufzeichnungen so dringend als Lesestoff empfohlen werden? Die Pest ist wieder da, diesmal wie damals aus China angekommen; aber während sie damals Jahre benötigte, den Weg aus China über Zentralasien und nach England zurück zu legen und noch dazu ein paar Jahrhunderte im Umlauf blieb, kam sie in ihrer heutigen Gestalt, als Covid-19, innert weniger Tage in Europa an.

Wie das möglich war? Du hast eine Karriere als Verwalter im Marineamt aufgebaut, in Verhandlungen kanntest Du Dich aus, aber der Handel hat sich inzwischen auf den ganzen Planeten ausgeweitet, und die Schoner und Dreimaster des 17. Jahrhunderts sind Luftschiffen gewichen, die jeden Tag Zehntausende von Reisenden von anderen Kontinenten zu und von den beiden großen sogenannten »Flughäfen« von London befördern.

Von meinem kleinen Bauerndorf im Zürcher Oberland aus stehe ich mittels eines ausgetüftelten Apparats mit unzähligen Menschen in Kontakt und obwohl Versammlungen von mehr als fünf Leuten verboten sind und vom Reisen strengstens abgeraten wird, erhalte ich laufend Nachrichten aus der ganzen Welt.

An Deinem täglichen Leben hast Du zu Pestzeiten wenig geändert. Die größte Sicherheitsmaßnahme hast Du für Deine Frau getroffen, als Du sie in das die Themse abwärts gelegene Woolwich geschickt hast; soziale Distanzierung in einem entfernten Dorf war das, „Selbstisolierung“ wohl nicht.

Die Pest wird in Deinem Tagebuch zum ersten Mal am 24. Mai 1665 erwähnt: »Von da mit Creed zum Kaffeehaus, das ich seit langem nicht mehr besucht habe — wo alle vom Rückzug der Holländer reden — und von dem Heranwachsen der Pest in dieser Stadt und von den Arzneimitteln dagegen; einige sagen dies, andere jenes.«

Am 10. Juni wird Deine Wachsamkeit schon größer, unter den Opfern sind Bekannte von Dir: »Nach drei oder vier Wochen ist die Pest in der Stadt angekommen, aber wo soll es begonnen haben, wenn nicht bei meinem guten Freund und Nachbarn, Dr. Burnett in Fanchurch Street.« Am nächsten Tag ist die Haustür vom armen Dr. Burnett zu: »Er hat aber großes Wohlwollen unter seinen Nachbarn geerntet; da er es als Erster entdeckt hat und sich freiwillig hat einschließen lassen.« Der Eintrag vom 25. August kündigt den Tod von Dr. Burnett an.

So hautnah erlebe ich den Tod in Zeiten des Covid-19 nicht, aber ich bleibe trotzdem, wie vom Bundesrat aufgefordert, zu Hause. Du hingegen bist die ganze Zeit unterwegs, als Sekretär, auch als Heiratsvermittler (wobei die Hochzeit wegen der Pest abgesagt werden musste; übrigens passiert meiner Mutter und ihrem neuen Partner genau dasselbe —heute heiraten Leute mit über 70 noch, weißt Du!), nach Woolwich hin und zurück (»All diese wichtigen Personen fürchteten sich vor London, argwöhnisch gegenüber allem, was von dort kommt [...] Ich musste ihnen erzählen, dass ich in Woolwich sesshaft war.«), spielst Billard, schläfst in verschiedensten Gasthäusern. Zu Deinen vielen Beschäftigungen gehören auch Flirten und Seitensprünge mit Schauspielerinnen: Du beschreibst diese liaisons in einer scheinprüden, leicht entzifferbaren Mischung von Spanisch und Französisch.

Gleichzeitig erzählst Du lapidar von dem Aufhäufen der Toten: in der Woche vom 15. Juni »sind an der Pest 112 gestorben, 43 die Woche davor«; am 29. Juni »beträgt die Sterblichkeitsrechnung 267« und »der Hof ist voll von Fuhrwerken und Menschen, die dabei sind, die Stadt zu verlassen«; in der Woche vom 20. Juli sterben 1'089 Menschen und am 31. August sind es bereits 6'102. Am 26. Juli denkst Du daran, ein Testament aufzusetzen.

Woher erfuhrst Du diese Zahlen? Durch die unzuverlässigen searchers of the dead — oft arme, alte Frauen, erkennbar an ihren weißen Stöcken, die in betroffene Haushalte eintreten und deshalb gesondert leben mussten? Hast Du an die Ziffern geglaubt? Hattest Du eine Ahnung, wie viele Leute außerhalb von London der Pest zum Opfer gefallen sind? Die Zahlen sind ungeheuerlich, vor allem im Verhältnis zu einer Stadtbevölkerung von einer halben Million (London zählt heutzutage über 8 Millionen Einwohner!). Ab und zu spürt man Deine Betroffenheit, eine Pause bevor Du Dich anderen Angelegenheiten zuwendest.

Wir, Bürger des 21. Jahrhunderts, sind in der Lage, die Zunahme der Infektionsraten und der Totenbilanz jede Minute zu verfolgen, und zwar überall auf der Welt, von Amerika bis zu den Antipoden (die zu Deinen Lebzeiten noch nicht »entdeckt« worden waren). Das Ganze ist sehr bedrückend, aber irgendwie irreal: für Dich muss es noch unverständlicher gewesen sein – unsere Mediziner wissen ja, wie sich Epidemien ausbreiten –und doch hast Du das Abriegeln der Häuser, die Beseitigung der Kadaver, die Verwandlung der Brachen außerhalb der Stadtmauer in Friedhöfe mit Deinen eigenen Augen beobachtet; zum Glück müssen wir das nicht mit ansehen, nur lesen, wie sich lang und schmerzvoll und einsam das Dahinsiechen hinter den Mauern der Krankenhäuser und Altersheime vollzieht.

Und die Welt draußen in den Straßen Londons beschreibst Du so: »Aber wie wenig Leute ich jetzt sehe, und diese laufen wie Menschen, die von der Welt Abschied genommen haben.« Von der Bootsreling aus siehst Du Menschenmengen an Beerdigungen und Scheiterhaufen am Ufer der Themse.

Am 30. September, als die Epidemie schon am Abflauen war, schreibst Du folgendes: »Ich muss sagen, dass, was Freude, Gesundheit und Gewinn betrifft, die letzten drei Monate bei weitem die besten, die ich in einer Periode von zwölf Monaten je erlebt habe [...] außer der großen Pest gab es nichts, was mich martern konnte.«

Die letzte Erwähnung von der Pest im Jahr 1665 lautet am 22. Dezember so: »Das Wetter war frostig kalt diese vergangenen acht oder neun Tage, also hoffen wir in der nächsten Woche auf eine Abnahme des Pest; andernfalls mag Gott uns gnädig sein, denn sonst wird die Pest sicher nächstes Jahr andauern.«

Dann war es aber vorbei, kaum noch eine Spur davon in Deinen Aufzeichnungen. Und das spendet mir Hoffnung, gerade in einer Zeit, als Regierungen hier eine allmähliche Lockerung der Ausgangssperre in Aussicht stellen.

Vielleicht erzähle ich Dir später vom Nachher . . .

Mit vorzüglicher Hochachtung

Simon Pare

PS. Da selbst mein Wahnsinnsapparat nicht jedes Buch aus den Bibliotheken bis hierher in mein Covid-Schlupfloch zaubern kann, musste ich Deine Tagebucheinträge selber übersetzen. Mögen deutschsprachige Leser und Leserinnen es mir verzeihen!

17—22 February 2020 Atelier de traduction ViceVersa au CITL Arles

Six seven-hour days of discussions with five Francophone and five Anglophone translators working on texts ranging from Langston Hughes of Harlem Renaissance fame to André Breton, a treatise on hunger to a YA novel, the poetry of Amy Clampitt, the dark humour of Donal Ryan, enslaved migrants on the shores of the Mediterranean, the French hinterland of Jeanne Benameur ... Such a wealth of registers to explore with our twelve-fold brain power.

Oh, and the light of Arles in February. Cycling in the Camargue. Vegetarian tiffin boxes out on the terrace. The beautiful Collège des traducteurs in a former cloister.

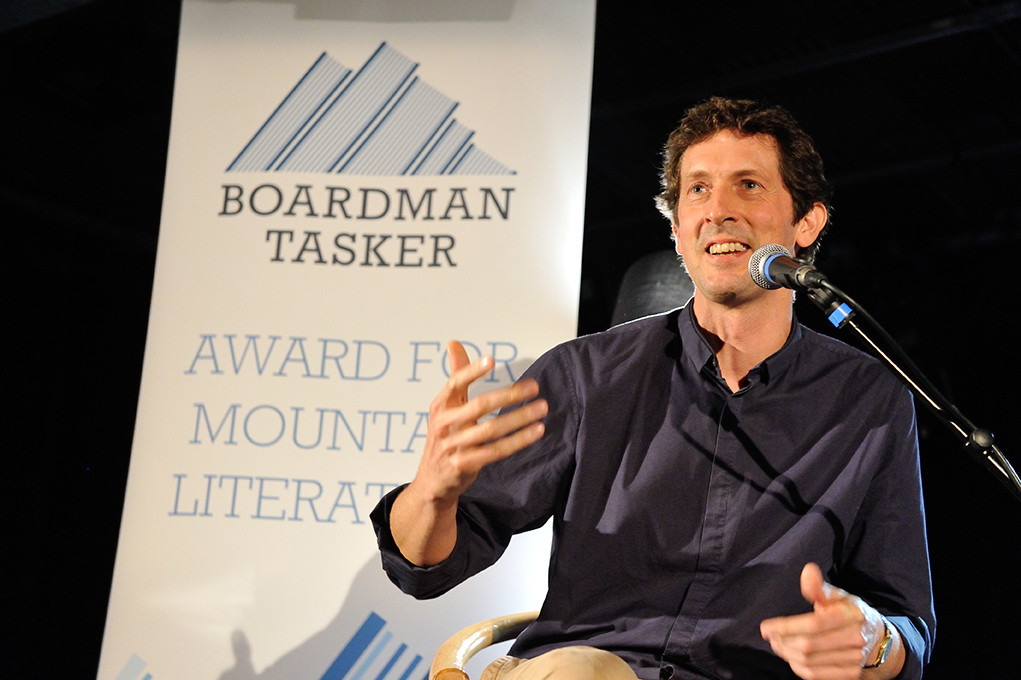

16 November 2018 2019 Boardman Tasker Award for Mountain Literature

Photos: Henry Iddon

16 March 2018 10 Jahre Traduki

Bolted Places, Airy Halls

On the Translator’s Art

Occasionally, when he thought he was alone or at least unobserved, my father would hold long soliloquies in a mysterious language not a word of which I could understand. Probably a year or two before I learned to read and write I began to eavesdrop on these secret monologues from an undiscoverable hiding-place. It was only years later, after I had attended school for some time, that I gradually worked out that the guttural sing-song of those speeches, so different in tone from the Upper Austrian dialect in which I was praised, comforted or scolded, was the melody of the Russian language. My father spoke Russian when he was alone, but it will remain for ever a mystery to me whether this stemmed from an enduring love for a country and its literature, awoken in him at an early age by one of his secondary-school teachers in defiance of the rampant zeitgeist, or whether he was still under the spell of his memories of a prisoner-of-war camp on the Crimean peninsula near Sevastopol. But one summer’s day he died on a bench waiting for a bus, and the time for asking him questions was over.

Recalling my scheme to eavesdrop on his soliloquies, I see myself crouching behind a washing basket with bated breath, racked with guilty curiosity, and yet compelled to return again and again by the alluring magic of a language that seemed to me at the time to be the authentic idiom of adulthood, from which only children were excluded. This language, I believed, would over time accrue to everyone as naturally as height, grey hairs, a beard, baldness and all the other signs of maturity. I merely had to be patient, I needed only to wait, and one day I too would understand this melody. What I overheard from my den belonged to the vocabulary of the future.

My father’s favourite place for raising his secret voice was the ‘English closet’ of a teachers’ hostel, painted the same yellow as Schönbrunn Palace and built long before to mark his Apostolic Majesty Franz Joseph I’s seventieth jubilee; it accommodated the primary school teacher of my home village. Every day of my first few years at school I would walk across its gravel yard to the schoolhouse opposite, often hand in hand with my father, but each time, upon reaching an invisible boundary in the centre of the court, I was obliged to set aside all private forms of address and, with the respect demanded of every pupil, call my father ‘Mr Ransmayr’ and ‘Sir’ until we got home.

Yet when this gentleman changed back from a teacher commanding esteem, obedience and attention into a kindly man who pulled me on a sledge across snowy fields, told me stories and taught me to swim in the calm waters below the rapids of a nearby river, he would also revert to being a man who, like me, had to obey the call of nature and withdraw to the English closet from time to time. Then, whenever possible, I would take up position in an adjacent cabinet whose door also displayed the ‘00’ room number commonly used for lavatories, even though its seatless, dusty porcelain bowl served solely to hold a huge wicker basket. I would then listen through a hole in the wooden partition to monologues accompanied by the unspeakable, forbidden sounds of a taboo-laden physical performance – a trumpet-punctuated water music that made my nosiness seem even more wicked.

Patience! I was convinced that I merely had to wait and let time pass, growing bigger and older, until the mysteries of this strange language and all the other freedoms of adulthood would reveal themselves to me—freedoms so boundless that they would even erase the transgressions of youth.

I remember my disappointment when, after countless return journeys across the playground, I had finally mastered the whole alphabet and fully expected it to unlock any book I wished—and yet could only stare in bewilderment at a row of books from my father’s library, for despite my newly acquired skills I was incapable of deciphering even the titles on their spines.

When I eventually dared to ask my father for help, he read their embossed hieroglyphs as effortlessly as I did my textbooks, and for the very first time I heard the melody of his secret language elsewhere than in a forbidden place; and embedded in that melody I heard, also for the first time, names such as Dostoyevsky, Pushkin, Gogol, Turgenev and Gorki. My toils of the past months may have given me mastery of the Latin alphabet, I realised, but I was worlds away from understanding Cyrillic, Arabic, Hebrew, Japanese, Chinese and any of the countless other lines of characters in which the world’s many languages became writing.

I can only dimly recall the revelation of this Babylonian fact. Far clearer in my mind, however, is the associated, painful and sobering realisation that to gain an understanding of language and writing was either inextricably bound up with the effort of learning or else required help, and that gifts such as one’s mother tongue were the exception. Normally, every single word would have to be heard and parroted, spelled and repeated over and over and over again until eventually it assumed a stable sound, a meaning and a distinctive shape.

And today? Today I know that our capacity to decipher the languages, tales and symbols of other cultures, whether they be budding far away, blossoming next door or long since faded, can be gifted even to people trapped in their mother tongues – if they are assisted by translators, interpreters and teachers, who regard their services not as a luxury but as a necessary and precious tool for understanding the world. Without this aid, even great literature would, to the vast majority of readers or listeners, be not a polyphonic choir singing in airy halls but merely a name for a series of soliloquies in occupied, bolted places.

26—30 June 2017 15th Straelener Atriumsgespräch on 'Cox'

Previous guests include Günter Grass (who inspired these Straelener Atriumsgespräche with his famous ritual of convening his translators for each new novel), Julia Franck, Jenny Erpenbeck, Lutz Seiler and Uwe Tellkamp.

I was lucky enough to be invited as the English translator of Christoph Ransmayr’s 2016 novel 'Cox oder Der Lauf der Zeit' (S. Fischer) for Seagull Books (who also published my translations of his previous two books, 'Atlas of an Anxious Man' and 'The Flying Mountain'), and we were all fortunate that Christoph found time in his hectic travel schedule.

The size of the groups has varied from three to eighteen in the past, and this year there were six of us, the other translators hailing from Bulgaria, Croatia, Italy, Spain and China.

It is unusual for a Chinese translator to participate in the Atriumsgespräch, but for this book Han Ruixiang’s presence was both significant and extremely helpful. After all, Cox centres on a fictional encounter between a late-18th-century English clockmaker, Alister Cox, and the Emperor of China, who has summoned him to his court to fashion a number of unique clocks, each reproducing a subjective perception of time. It is a wonderful evocation of two men’s attempts to master the passing of the years, of love and loss, with occasional flashes of recognition and understanding piercing the mysterious veil of cultural and social differences.

Under the guidance of literary critic Insa Wilke, we started by addressing some general aspects of the novel (unorthodox punctuation, pronunciation and transliteration of Chinese terms, titles, etc.) before working our way through the book from first page to last, raising queries as we went. It is a short novel, and Christoph Ransmayr writes with great clarity, so progress was swift and we’d tackled all our queries by lunchtime on the second day. As a seasoned traveller, Ransmayr is extremely alive to the subtleties of translation and interpretation, and his overall message was that we could do much as we wished. He even provocatively suggested that we embellish his novel with some scenes of our own devising.

Ruixiang was troubled by the fact that some geographical details about China – the course of a river, the name of a sea – were deliberately distorted in the book: a Chinese reader wouldn’t understand. Christoph Ransmayr’s response? Change whatever needs changing! Other questions from Ruixiang went more to the heart of differing Western and Chinese worldviews. For example, why should a court mandarin feel trepidation when his sole function was to obey orders? And so, in translating, we experienced a little of Cox’s bewilderment faced with a foreign culture.

The trouble with gathering several translators working in different languages is that, in the absence of many difficulties of understanding, each of us was left with the problem of how to make the book sing in our particular language – and non-native speakers cannot help you with that. For languages less dense than German, the major challenge of reproducing Ransmayr’s writing in English is the need to unravel extremely long sentences while maintaining his singular cadence.

In general, I am convinced that translating is a very private pursuit, an individual grappling with a text. The great joy of collaborating in this way, though, is that people have interesting anecdotes to tell and unexpected areas of knowledge come to light. In our case, Andy Jelčic from Croatia turned out to be an expert on clocks, so we benefited from a potted history of clock mechanisms during a visit to the town museum.

The climax of the workshop was a public reading in the College’s wonderful atrium to a mixed audience of some eighty-five dignitaries, funders, local booklovers and resident translators. Christoph Ransmayr discussed the book and his admiration for translators, then read the first page of the novel, which describes Cox’s arrival by ship in Hangzhou Bay just as twenty-seven tax collectors are having their noses cut off on the quayside. Each of us then answered a question from the moderator before reading our own version of the same passage, creating a staggered chorus of Coxes, some intelligible to many, some a blaze of sound. Ransmayr read the rest of the first chapter – then drinks rounded off a collaborative, cosmopolitan occasion during which we had eaten together, laughed together, cycled through a nature reserve into Holland for pancakes and local beer, and talked literature, travel, poker, showjumping and other matters too numerous to mention.

It should be mentioned that Renate Birkenhauer kept detailed minutes which will serve as a record for the book’s future translators into other languages and colleagues who were unable to attend.

A final word about the Europäisches Übersetzer-Kollegium for those unfamiliar with it. As well as hosting the Atriumsgespräche, the centre is a fantastic place for translators (with a book contract) to come and work for anything from a couple of weeks to three months in the case of the translator-in-residence. I would like to thank Frau Dr. Regina Peeters and her kind team who think of everything, leaving you to enjoy the facilities (including the largest dedicated translation library in the world), the peace, the bikes (the surroundings are tabletop flat!) and a studious community of interesting, like-minded colleagues.

Article published in New Books in German